Photos That Shaped History: Why Photojournalism Still Matters

Views & Reviews: essays and book reviews

The decline of traditional journalism, particularly in newspapers, marks a seismic shift in how society understands itself and the world. Once a trusted cornerstone of public accountability and shared memory, print journalism has steadily eroded under the weight of economic challenges, technological disruption, and changing media consumption habits. With this decline comes the slow demise of photojournalism—a vital component of visual storytelling that has long provided an irreplaceable lens on history, humanity, and truth.

Nowhere is the power of photojournalism more apparent than in the iconic images that have shaped modern memory. Four such photos stand out as evidence of its singular ability to capture moments of profound tragedy, transformation, and urgency. I have selected these photos because of the profound impact they had on me at the time. Almost 60 years later, I still experience a range of deep emotions when I view them. I am confident that many readers of this essay have the same experience.

Images That Defined History

The first image photographed by Walt Cisco occurs a moment before the assassination of President John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963. Captured on the streets of Dallas, this moment—whether seen in still photographs like this or through Abraham Zapruder’s home film—marked a nation’s heartbreak. In this photo, the motorcade moves forward surrounded by a cheering crowd, unaware that history is about to fracture. The shocking immediacy of this and other images conveyed a truth more powerful than any written account: the fragility of life and the way history turns on a single moment.

Following that tragedy, another indelible photo emerged aboard Air Force One. As Lyndon B. Johnson stood with his hand raised, taking the oath of office beside Jackie Kennedy—her pink suit stained with her husband’s blood—the photo captured a nation caught between grief and continuity. Cecil Stoughton’s image speaks volumes: power and sorrow side by side, a visual reminder of America’s resilience in its darkest hour. Without this photo, the quiet poignancy of that transition might have been lost.

A decade later, in Vietnam, an image would appear that pierced the conscience of the world. On June 8, 1972, Nick Ut photographed Phan Thi Kim Phuc, the “Napalm Girl,” running naked and screaming in agony after a napalm attack. The photo stripped war of abstraction, forcing the world to confront its human toll. In one image, Ut exposed the brutality of conflict and gave an innocent victim a global voice. The image reverberated far beyond the battlefield, helping turn public opinion against the war itself.

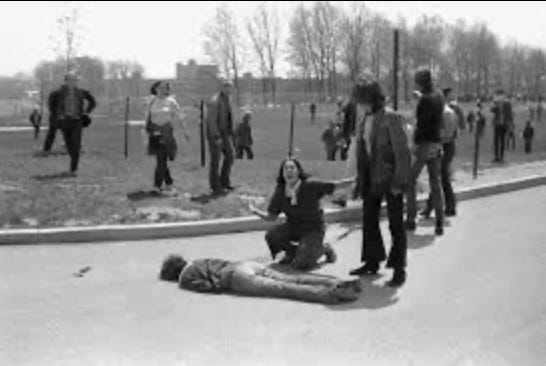

Similarly, John Paul Filo’s Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph from the Kent State University shootings on May 4, 1970, became an eternal emblem of domestic unrest. A young woman kneels, anguished, over the body of a student killed by National Guardsmen during a protest against the U.S. invasion of Cambodia. Her outstretched arms and open mouth wordlessly express the grief, confusion, and fury of a generation. It is an image of accountability—a demand that the world witness the price of political decisions.

These photographs endure not merely because they depict significant events but because they distill entire stories into a single frame. They are more than visuals; they are touchstones of truth, empathy, and collective memory.

Why Photojournalism Is Dying

In the heyday of newspapers and magazines, professional photojournalists were essential to storytelling. They did more than take pictures—they bore witness to history, embedding themselves in events, often at great personal risk, to capture the moments that words alone could not convey. Their work required time, skill, and ethical commitment to the truth.

Today, however, photojournalism has become collateral damage in the broader decline of print journalism. The collapse began with the digital revolution, as news migrated online and readers turned to free, easily accessible content. Advertisers followed suit, moving to digital platforms where companies like Google and Facebook offered more targeted, cost-effective campaigns. Newspapers, once sustained by classified ads and subscription models, saw revenues plummet. Cost-cutting became inevitable, and photo departments were among the first to be downsized or eliminated.

The rise of smartphones and social media further eroded the role of professional photojournalists. In theory, everyone with a phone now has the power to document events as they unfold. Citizen journalism has provided some extraordinary images in moments of crisis, but it cannot replace the intentional storytelling that photojournalists provide. A photojournalist does not merely capture a moment—they seek out context, meaning, and composition to deliver a narrative. Without their skill and ethical rigor, photography risks becoming a spectacle rather than a record of truth.

The Loss of Visual Memory and Accountability

The decline of photojournalism has serious consequences for society. Photographs, unlike other forms of media, transcend language and time. They evoke emotion, inspire action, and demand that we bear witness. Without professional photojournalists, fewer images will rise to the level of those four iconic photos: fewer moments of anguish, courage, or injustice will be etched into the collective consciousness.

The absence of these images weakens journalism’s role as a watchdog. Photographs hold power to account in ways that words often cannot. When Nick Ut’s “Napalm Girl” or Filo’s image at Kent State appeared, they forced the public to confront truths that were otherwise easy to ignore. Without professional photojournalists at work, who will document today’s wars, protests, or moments of political transition with the same clarity, credibility, and emotional depth?

Moreover, the loss of photojournalism threatens to erase history itself. Iconic images like those of Kennedy’s assassination or LBJ’s swearing-in endure not because they were shared quickly but because they were captured deliberately, distributed widely, and preserved with care. Today’s fragmented visual culture—driven by social media algorithms and fleeting attention spans—lacks this permanence. Images that deserve to be remembered risk being buried in the noise, lost to the ephemera of the digital age.

A Call to Preserve Photojournalism

The decline of photojournalism is not inevitable; it is a choice. Media organizations must recognize that visual storytelling is not an expense but an investment in truth and history. Audiences, too, play a role: supporting journalism through subscriptions, donations, and engagement with meaningful, ethical content rather than click-driven spectacle.

As the world grows more complex, we need photojournalists more than ever. They are the custodians of our shared memory, the witnesses who ensure that history is seen, felt, and remembered. Without their images, moments of tragedy, transformation, and triumph risk fading into obscurity.

The four photos—of Kennedy, LBJ, the “Napalm Girl,” and Kent State—remind us of what we stand to lose. They are not just relics of the past; they are proof of the enduring power of photojournalism. They challenge us to preserve this vital craft for future generations, lest we lose not only the images but the truths they carry.

(The author received a B.A. degree in Philosophy from The Johns Hopkins University and a Juris Doctor degree, with Honors, from The George Washington University Law School.)

My mind turns automatically to the Kent State photograph when I hear Trump and his cult members discussing turning our military on us. We are on display for all the world to witness. Dumbing down the populace is going to have many unintended consequences. It’s up to us to save our country. Too much is at stake to shrug it off.

Marc Friedman: At 77, these photographs are contemporary events in my life, and the shock is fresh with each look at the picture.