This is an important book. Dara Horn’s People Love Dead Jews: Reports from a Haunted Present is a brilliantly provocative and deeply unsettling book that forces readers—Jewish and non-Jewish alike—to confront the ways in which societies sanitize and commodify Jewish suffering while largely ignoring or even perpetuating ongoing antisemitism. Horn, an acclaimed novelist and scholar, delivers a collection of essays that is both fiercely intelligent and unapologetically candid, weaving historical analysis with personal reflection to expose a painful but essential truth: many people are far more comfortable honoring dead Jews than respecting or protecting the living ones.

Horn’s thesis is straightforward yet profoundly disturbing. In a time when antisemitic incidents are on the rise globally, and historical revisionism is increasingly prevalent, her argument serves as a crucial wake-up call. The persistence of antisemitic violence, the distortion of Jewish history for non-Jewish audiences, and the selective memory surrounding Jewish suffering make her message more relevant than ever. She argues that while public commemorations, museum exhibits, and literary tributes to Jewish tragedy abound, contemporary antisemitism is often minimized, dismissed, or even encouraged. Through a series of essays exploring topics as diverse as Holocaust memorialization, Anne Frank’s posthumous fame, and the erasure of Jewish identity in mainstream culture, Horn reveals the many ways in which Jewish history is repackaged for non-Jewish consumption—often in ways that distort its meaning and undermine its lessons.

A Shocking Yet Necessary Revelation

From the outset, Horn challenges the reader with uncomfortable truths. In her opening essay, she recounts an assignment for “Smithsonian Magazine” in which she was asked to visit the site of a Jewish community that had been wiped out by history. The request itself encapsulates the book’s central irony: Jewish history is often more palatable to the world when it is about loss rather than survival. Horn notes that while non-Jews frequently profess admiration for dead Jews—from Anne Frank to the victims of pogroms and the Holocaust—they often bristle at the presence of living Jews who assert their identity or demand justice.

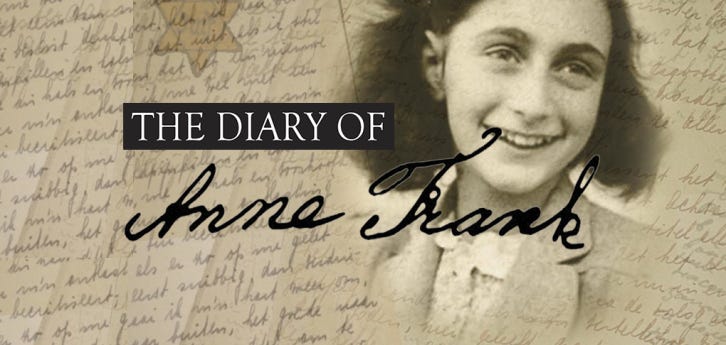

One of the book’s most devastating sections examines how Anne Frank’s diary has been transformed from a powerful document of Jewish suffering into a feel-good story about resilience and forgiveness. A particularly striking example is the 1955 Broadway play The Diary of Anne Frank, which downplayed Anne’s Jewish identity and omitted many of her most pointed observations about antisemitism. By softening her story for a universal audience, such adaptations have often stripped it of its historical and cultural specificity, transforming the diary from a powerful document of Jewish suffering into a feel-good story about resilience and forgiveness. Horn argues persuasively that this pattern is not unique to Anne Frank but reflects a broader cultural tendency to commemorate Jewish tragedy in ways that make it digestible for non-Jews while ignoring the actual causes of that suffering.

Antisemitism in Plain Sight

Horn also takes aim at the widespread reluctance to acknowledge contemporary antisemitism. In a particularly chilling essay, she recounts the 2019 attack on a kosher supermarket in Jersey City, where gunmen targeted Jewish victims explicitly because they were Jewish. Despite this, much of the media downplayed the antisemitic nature of the attack or framed it in ways that minimized Jewish suffering. Similarly, she discusses the 2018 Tree of Life synagogue massacre in Pittsburgh, noting how the world briefly mourned the victims before moving on—without any serious reckoning with the deep-rooted antisemitic ideologies that led to the attack.

Horn sharply critiques how society often normalizes or downplays the murder of Jews, treating it as an almost expected occurrence rather than an urgent crisis demanding immediate action. She points to the shocking lack of outcry over a spate of violent attacks on visibly Jewish people in places like Brooklyn and Paris. Unlike other forms of bigotry, which elicit widespread condemnation, antisemitic violence often fails to provoke the same level of outrage. Horn astutely observes that part of this stems from a broader cultural tendency to see Jews as eternal outsiders, whose suffering is either deserved or simply an inevitable part of history. By contrast, hate crimes against other marginalized groups tend to generate immediate public outcry and institutional responses. This stark discrepancy underscores a troubling societal double standard in addressing different forms of bigotry, further reinforcing Horn’s central argument.

Historical Amnesia and the Whitewashing of Jewish Identity

Another powerful theme in People Love Dead Jews is the erasure of Jewish identity in narratives of persecution. Horn examines how Jews have been posthumously transformed into symbols that serve other people’s agendas. She highlights the case of Varian Fry, an American who heroically helped Jews escape Nazi-occupied Europe. Fry’s story is often celebrated, but as Horn points out, the Jewish refugees themselves are frequently reduced to nameless figures in the background. Their actual lives, beliefs, and identities are overshadowed by the focus on the non-Jewish rescuer.

Similarly, Horn critiques the way Jewish history is sometimes rewritten to fit broader, non-Jewish narratives. She discusses the way Soviet Jews’ experiences of persecution were downplayed in favor of a more generic “victim of communism” framework, erasing the explicitly antisemitic nature of their oppression. Even in Holocaust education, Horn argues, there is often a reluctance to acknowledge the specificity of Jewish suffering, as some prefer to universalize the lessons in ways that diminish the uniquely Jewish experience.

The Ongoing Relevance of Horn’s Message

Horn’s book is not just a critique of how history is remembered—it is a warning about the present and the future. Antisemitism is on the rise globally, from violent attacks in the United States and Europe to the spread of conspiracy theories online. Horn’s essays make it clear that while people may claim to “never forget” the horrors of the past, their actions often tell a different story.

This book is particularly urgent today, as Jewish communities worldwide face renewed threats from both the far right and the far left. Recent years have seen a surge in violent attacks, from the 2018 Pittsburgh synagogue shooting to the 2022 hostage crisis at Congregation Beth Israel in Texas. More than 10,000 antisemitic incidents occurred in America between the Hamas attack of October 7, 2023, and September 2024 - up from 3,325 incidents the prior year.

Meanwhile, antisemitic conspiracy theories proliferate online, fueling dangerous rhetoric that translates into real-world violence. Whether it is violent white supremacists chanting “Jews will not replace us” in Charlottesville, or anti-Zionist activists like Kanye West using rhetoric that veers into outright antisemitism, the modern world continues to treat Jews as a problem to be solved rather than a people with the right to exist safely and freely. Horn’s analysis forces us to ask difficult but necessary questions: Why does antisemitism persist across the political spectrum? Why is Jewish suffering so often viewed as more legitimate when Jews are powerless rather than when they defend themselves? And why do so many people express sympathy for dead Jews while ignoring or even enabling the hatred directed at living ones?

Perhaps most importantly, Horn’s book challenges the idea that remembering the Holocaust or past pogroms is enough. As she compellingly argues, commemoration without action is hollow. It is easy to praise Anne Frank, but much harder to stand up for Jews who are alive today and facing harassment, discrimination, or violence. True moral responsibility requires more than passive remembrance—it demands active engagement in fighting antisemitism in all its forms.

Conclusion: A Vital and Unflinching Work

People Love Dead Jews is a searing, necessary, and deeply affecting book. Horn’s incisive prose and unrelenting honesty make for an unforgettable reading experience, one that refuses to let the reader look away from uncomfortable realities. This is not a book that offers easy solutions or comforting reassurances. Instead, it forces readers to confront the painful truth that much of the world’s relationship with Jewish history is built on a foundation of hypocrisy and selective memory.

Horn’s work is an urgent call to recognize and challenge antisemitism in all its manifestations, consistently and without hesitation. Beyond reading this book, readers can take meaningful action by educating themselves on contemporary antisemitism, speaking out against antisemitic rhetoric and violence, supporting Jewish organizations, and advocating for policies that promote tolerance and historical accuracy. consistently and without hesitation. In an era where historical amnesia and willful ignorance continue to fuel prejudice, People Love Dead Jews stands as a powerful reminder that remembering the past is not enough—we must also protect the present and the future.

This is a book that deserves to be widely read, discussed, and, most importantly, acted upon.

Well reviewd., thanks. Blunt message about relegating antisemitism to the safety of history while irgnoring with a modicum of tut-tuts present day anti-Jewish screeds, actions, and baked in prejudices. I wonder if the same can be said of anti-Black sentiment. We honor MLK, Muhammad Ali, Thurgood Marshall, James Baldwin, Malcolm X, etc. because they are safely in their graves.

Marc, an important book well reviewed. But at the risk of seeming to be self-serving, I’d like to point you to this small volume.

https://a.co/d/jhX7JIc

The lead story called “Shema” follows a 13 year-old Jewish girl 500 years in the future who watches her family’s government sanctioned murder by the “New Christians” and while using a computer to search for the long lost meaning of Shema, is discovered and killed herself after having become the last Jew. The story is my granddaughter’s debut story having been published when she was just 16.